Language is now the medium of choice in art schools.

Rob Colvin, Hyperallergic

I read a lot of writing by artists; manifestos, statements, quotes, interviews, and I listen to or watch artists speaking lucidly about their process and ideas in documentaries, conferences, and elsewhere. There is a school of thought that artists don’t write (they do) or need to speak about their work (they do). And it follows that there is also a school of thought that the work of art must stand on its own and “speak” for itself. While I think that might be possible in some cases and art in certain circumstances needs no help from language, it is increasingly evident that art and language are a part of a system, each reliant on the other for its traction or rootedness. As art is created in the contemporary era, it has become more complex, more boisterous, and more conversational. Even in quietude, in work that is deeply personal and meditative, there is language affixed to the image, sometimes pages of language that offer us a glimpse into the nuanced individual narrative that inspired such work. So much language would seem to belie the idea that a work of art should be self-explanatory, that it should speak for itself. But art at its most personal often needs further explanation. The turn from the universal to the personal seems on its surface to be a recent phenomenon. It is, however a constant in art since the earliest days of Modernism.

As evidence of my claim for the capacity of artists to put into language the very ideas that their “work” addresses in form, one need only only to peruse Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art, A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings by Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz. It contains 1168 pages of artists’ writing from the early 20th century to present, and makes it clear that word, that language in general, is an indispensable corollary to the objects of art-making themselves.

The move from the universal to the personal has a referent in literature in the form of the memoir, the first-person account of one’s own life. Neither fiction nor novel, the memoir is narrative nonetheless, an intimate product of lived experience. Artists have certainly written memoirs, though in the post-modern era much of what we see in museums and galleries and in art schools is a kind of objectified memoir. Such work is often launched into being by a particular life-experience and is thus a kind of memorialization of that experience, a memoir in three (or four) dimensions. I am thinking of work by Tracy Emin for instance, whose life has been considerably shared in installations including the now infamous My Bed, first featured in Tate Britain’s 1999 Turner Prize exhibition.

My Bed by Tracy Emin, 1998

While Emin’s My Bed, (a confessional self-portrait of objects that featured stained sheets, used condoms, cigarette butts, and empty vodka bottles) might have indeed “spoken for itself,” Emin has certainly spoken and written about the piece almost non-stop since its unveiling, filling in the narrative of the work and expanding the public’s understanding of the often polarizing project. Other artists whose creative output is perhaps less confrontational also speak at length about the origins and multiple meanings embedded in their work.

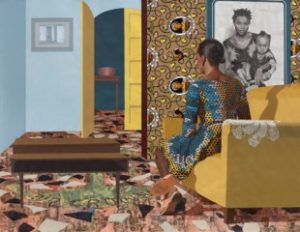

Mother and Child by Njideka Akynyili Crosby, 2016

In a short documentary by SFMOMA, Njideka Akynyili Crosby talks about the moment in her painting when her “Nigerianness and her Americanness collide.” A hybrid of dual cultures the artist applies her traditional European-style art training to issues of the most personal and

intimate nature; home, relationships, family, identity and the experience of her own life. Named a 2017 MacArthur fellow, Akunyili Crosby’s paintings of herself, friends and family, often seen in private spaces, address cultural hybridity through a number of portals. Images of popular Nigerian musicians collide with ads from fashion magazines and elsewhere, and while African viewers may be able to “decode” the images, Western viewers may need further unpacking of the ideas behind the work.

Czara z Babelkami by Ursula von Rydingsvard, 2006

In speaking about her work, the sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard often discusses her family’s history as Polish peasant farmers and World War II refugees, describing a difficult life, the memories of which are imprinted on her body and exorcised through the labor of her massive, haunting sculptures. In monumental works such as Czara z Babelkami, we get the sense that there is something unspoken about the provenance of the jagged, rough-hewn surfaces of the carved and constructed wooden monoliths. Reading von Rydingsvard’s own exposition about her life and the resonance of her personal experience illuminates her sculptures in a manner that enhances our empathy for all trauma and suffering as a result of political conflict and reinforces the relationship between gesture and language as two ends of the same spectrum.

Very best,

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department