We are deeply inside of a historical moment now, made vividly aware of the minutiae of the moment via 24/7 news and streaming media. So much so that it is, for me, overwhelming. I am also very aware of the aggregation of mediated images of the Covid-19 crisis into a kind of visual culture; of trauma, of heroism, of recovery, of pain, of the suffering of others. The tools of design and storytelling, of representation, and of the arts generally are put into use to open hearts, to create a culture of empathy and to keep us engaged at a granular level, such that we can recite arcane medical facts about curves and ventilators and PPE and pulse/ox levels. This is the arts (the narrative and visual arts, photographic and moving image, cinematic and sonic) being put to use in the most pragmatic way, vastly different than some examples of the arts as responsa to similar pandemics or cultural traumas.

We are deeply inside of a historical moment now, made vividly aware of the minutiae of the moment via 24/7 news and streaming media. So much so that it is, for me, overwhelming. I am also very aware of the aggregation of mediated images of the Covid-19 crisis into a kind of visual culture; of trauma, of heroism, of recovery, of pain, of the suffering of others. The tools of design and storytelling, of representation, and of the arts generally are put into use to open hearts, to create a culture of empathy and to keep us engaged at a granular level, such that we can recite arcane medical facts about curves and ventilators and PPE and pulse/ox levels. This is the arts (the narrative and visual arts, photographic and moving image, cinematic and sonic) being put to use in the most pragmatic way, vastly different than some examples of the arts as responsa to similar pandemics or cultural traumas.

I have been thinking about the difference between empathy and compassion lately. Empathy is viscerally feeling what another feels. Compassion starts with empathy but includes the act or remediation; the attempt to alleviate the pain of others. Artists have the unique ability to create the circumstances for contemplation of the pain of others and often make work that catalyzes healing on the part of the viewer. Compassion, as Deepak Chopra explains, is a renewable resource. I would add, even moreso in the hands of artists.

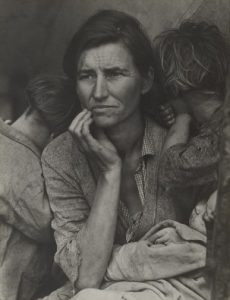

The quickly developed visual culture of the Covid-19 crisis is full of seductive graphics, zoom memes, and hero narratives that, while buoying the spirits of many, obscure the actual and real suffering of strata of people below the radar at the margins of culture, whose images do not support the stories that well-meaning media outlets wish to tell.  I am reminded of images by Margaret Bourke-White and Dorothea Lange, pictures taken during the dust bowl era, as a part of the population was thrust into poverty, homelessness, and migration, into a peripatetic and hopeless diaspora toward some unknown future.

I am reminded of images by Margaret Bourke-White and Dorothea Lange, pictures taken during the dust bowl era, as a part of the population was thrust into poverty, homelessness, and migration, into a peripatetic and hopeless diaspora toward some unknown future.

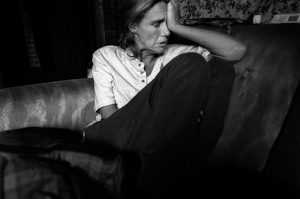

Artists create the conditions for an experience that allows us to see the world as it is.  I’m thinking about photographer Darcy Padilla’s images from the Julie Project in which she mediates the act of witnessing the lived trauma of her subject without heroicizing the moment; rather her camera records the moment with the graceful distance of the medium of photography and no overt attempt to create a weighted narrative of the event.

I’m thinking about photographer Darcy Padilla’s images from the Julie Project in which she mediates the act of witnessing the lived trauma of her subject without heroicizing the moment; rather her camera records the moment with the graceful distance of the medium of photography and no overt attempt to create a weighted narrative of the event.

Artists often swerve into the work of curation, and curators themselves are deeply engaged with presenting the work of artists in thoughtful and generous ways. The etymology of curation is closely aligned with the act of caretaking. As early as the 14th century, curate is defined as a “spiritual guide, ecclesiastic responsible for the spiritual welfare of those in his charge,” from Medieval Latin curatus “one responsible for the care (of souls),” from Latin curatus, past participle of curare, “to take care of.” To take care is at the root of curating. Such images made in the spirit of caring or caregiving, curated to engender feelings of hope, make palpable very real images of suffering.

I was able to sit with my mother at the end of her life and photographed her passing/transition from life to death. It was my way of coping with and witnessing her death. In the crisis of Covid-19, many of our citizens and the citizens of other countries make that transition alone and without witness or traces of the passing of their loved ones. Artists are often present in the absence of others and become surrogate witnesses for us.  Years ago, I had the opportunity to document a performance of a dance called Mourner’s Bench by Talley Beatty. Originally choreographed in 1947, it was Mr. Beatty’s signature solo and restaged for the opening night of the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina, on June 21st, 1990.

Years ago, I had the opportunity to document a performance of a dance called Mourner’s Bench by Talley Beatty. Originally choreographed in 1947, it was Mr. Beatty’s signature solo and restaged for the opening night of the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina, on June 21st, 1990.  Beatty’s work was inspired by Howard Fast’s Southern Reconstruction novel Freedom Road and “refers to the tragic influence of the Ku Klux Klan on a mixed-race community in the rural South after the Civil War. The soloist asserts himself within and against the themes of oppression and transcendence in the highly stylized, gestural vocabulary of the piece. Set to the traditional spiritual There Is A Balm in Gilead, the dancer, “sitting on the mourner’s bench,” reflects upon the end of his community and the horror of its slaughter.” (Source: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.) The seemingly simple, evocative work opens our hearts to suffering that we could not have witnessed, yet through the work of art, may feel empathy for.

Beatty’s work was inspired by Howard Fast’s Southern Reconstruction novel Freedom Road and “refers to the tragic influence of the Ku Klux Klan on a mixed-race community in the rural South after the Civil War. The soloist asserts himself within and against the themes of oppression and transcendence in the highly stylized, gestural vocabulary of the piece. Set to the traditional spiritual There Is A Balm in Gilead, the dancer, “sitting on the mourner’s bench,” reflects upon the end of his community and the horror of its slaughter.” (Source: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.) The seemingly simple, evocative work opens our hearts to suffering that we could not have witnessed, yet through the work of art, may feel empathy for.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department