I recently had the opportunity to sit in at a version of a “long table” discussion about generosity and art. The idea of the long table has been brought into a contemporary art context by the theater artist Lois Weaver, who based her version on Marleen Gorris’ film

I recently had the opportunity to sit in at a version of a “long table” discussion about generosity and art. The idea of the long table has been brought into a contemporary art context by the theater artist Lois Weaver, who based her version on Marleen Gorris’ film  Antonia’s Line, “in which the protagonist continually extends her dinner table to accommodate a growing community of outsiders and eccentrics until, finally, the table must be moved out of doors.” The image of a long table full of participants motivated to unfettered discourse is of course, resonant of how we might imagine a feast; fecund, plentiful, savory, delightful, and perhaps full of unknown flavors. It is in and of itself a generous image. And we do often think of art as a particularly generous space. Artists are often portrayed or imagined as creative individuals whose overflowing gifts are freely shared with a public and, in the extreme version, have little regard for the encumbrances of fiscal remuneration. Of course, this is a whimsical, fanciful notion. Artists may well be generous people, however, the objects created by artists are subject to and rewarded by a particular kind of market value.

Antonia’s Line, “in which the protagonist continually extends her dinner table to accommodate a growing community of outsiders and eccentrics until, finally, the table must be moved out of doors.” The image of a long table full of participants motivated to unfettered discourse is of course, resonant of how we might imagine a feast; fecund, plentiful, savory, delightful, and perhaps full of unknown flavors. It is in and of itself a generous image. And we do often think of art as a particularly generous space. Artists are often portrayed or imagined as creative individuals whose overflowing gifts are freely shared with a public and, in the extreme version, have little regard for the encumbrances of fiscal remuneration. Of course, this is a whimsical, fanciful notion. Artists may well be generous people, however, the objects created by artists are subject to and rewarded by a particular kind of market value.

When I think about generosity in the context of art, I think about the idea of the Samaritan in its biblical for as a person who does good deeds out of care or concern for others, without reward or recognition. Often recast in our contemporary culture as the good samaritan, there is an element of the performative in the selfless determination of such individuals, even a moral component to their actions. The old testament is replete with descriptions of charitable giving, good deeds, and selfless acts. Farmers are exhorted to set aside the corners of their crops during harvest for those without land, and there are texts devoted to enumerating how one gives help to others so as not to embarrass the recipient. Such gifts are to be made anonymously to insure a kind of purity of motive on the part of the donor or Samaritan. We can extrapolate these structures as the basis for extensive systems of social welfare combining individual initiative, charitable treatment of others and shared responsibility for the community at large.

At the long table, we talked about the possibilities of whether and how generosity co-exists with contemporary art-making practices, how collaborative practices support shared ideals of citizenship, and how a philanthropic gestures that on the surface seem to be generous may still accrue value to the philanthropist in seeming contradiction to the generosity of such selflessness. As one excavates the nature of generosity within the systems of commerce and capitalism, the desire for something we can take to heart as purely generous becomes fraught.

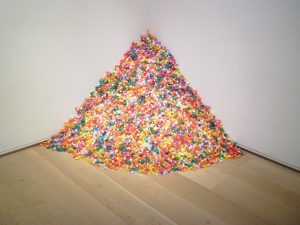

When I think about generosity in art, I immediately imagine Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work, made as a remembrance of his partner Ross, of an endless supply of candies individually wrapped in multicolor cellophane. It is indelibly etched in my memory for all the things I believe makes for such a gesture; it remembers, it is giving, it is available and it asks for nothing except your ability to receive the gift. I keep a small bag of the candies from the work on a shelf in my office. The sweet wrapped candies that are given freely to those who visit the artwork are replenished each time it is exhibited and I keep them as a talisman that reminds me of the possibility for art to indeed be the gift we wish for.

When I think about generosity in art, I immediately imagine Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work, made as a remembrance of his partner Ross, of an endless supply of candies individually wrapped in multicolor cellophane. It is indelibly etched in my memory for all the things I believe makes for such a gesture; it remembers, it is giving, it is available and it asks for nothing except your ability to receive the gift. I keep a small bag of the candies from the work on a shelf in my office. The sweet wrapped candies that are given freely to those who visit the artwork are replenished each time it is exhibited and I keep them as a talisman that reminds me of the possibility for art to indeed be the gift we wish for.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department