I have been thinking about the link between art and literature lately, mostly that it seems to have gone missing, or at least seems less prevalent than in other generations of art practice. The origins of ideas, the points of tangency of those ideas, and their provenance seems to have become diffused in the digital era. In the digital era, it becomes harder to track the provenance of ideas and their subsequent diaspora. Throughout recent art history, there has been a constant oscillation between the work of writers and the work of visual artists, each referencing the other and finding inspiration in the intertextual resonance of language and object. Often, the merging of art and language has been facilitated by the same person; here I am thinking about the Dadaists Tristen Tzara and Hugo Ball and the contemporary work of the artist Leslie Dill or the conceptual text work of Lawrence Weiner. All of these artists merged language with the optical and spatial considerations of objects or two-dimensional work. For other artists literature itself, in the form of poetry or music was the impetus for a kind of synesthesia intermingling of form and content.

I have been thinking about the link between art and literature lately, mostly that it seems to have gone missing, or at least seems less prevalent than in other generations of art practice. The origins of ideas, the points of tangency of those ideas, and their provenance seems to have become diffused in the digital era. In the digital era, it becomes harder to track the provenance of ideas and their subsequent diaspora. Throughout recent art history, there has been a constant oscillation between the work of writers and the work of visual artists, each referencing the other and finding inspiration in the intertextual resonance of language and object. Often, the merging of art and language has been facilitated by the same person; here I am thinking about the Dadaists Tristen Tzara and Hugo Ball and the contemporary work of the artist Leslie Dill or the conceptual text work of Lawrence Weiner. All of these artists merged language with the optical and spatial considerations of objects or two-dimensional work. For other artists literature itself, in the form of poetry or music was the impetus for a kind of synesthesia intermingling of form and content.

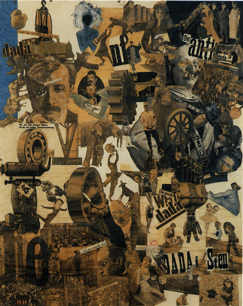

As an example, I am thinking about the assemblage and collage techniques in such work as Hannah Hoch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic, 1919, a collage of pasted papers and the detritus of everyday life. What do you see in this work? A field of vision in which all is equal, a space where the gesture of the image and multiple narratives collide with objects, people and place, through its use of language in the optical field.

As an example, I am thinking about the assemblage and collage techniques in such work as Hannah Hoch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic, 1919, a collage of pasted papers and the detritus of everyday life. What do you see in this work? A field of vision in which all is equal, a space where the gesture of the image and multiple narratives collide with objects, people and place, through its use of language in the optical field.

Such provisional relationships are even more pronounced in the symbiosis of the writers of the Beat generation and some of the early Punk bands on both the West and East coasts. The music of Patti Smith, Jim Carroll, and Henry Rollins has all been influenced in some form by writers such as William Burroughs and Kathy Acker, among others. Surrealism seems inextricably linked to its literary counterpart, Magic Realism most notably perhaps in the work of the Argentine writer, Jorge Luis Borges.

Charles Baudelaire, the modernist poet whose earliest work in the mid 1800’s took the form of art criticism wrote:

Romanticism and modern art are one and the same thing, in other words: intimacy, spirituality, colour, yearning for the infinite, expressed by all the means the arts possess.

For Baudelaire, modern life was inspiration for art, especially his romantic notion of what art could be and how it could be.

The painter Julian Schnabel has long aligned his work with literary figures, sometimes citing them within the painting as shards of texts or simply scrawling the names of well know literary figures across the canvas as a kind of signifier of allegiance to literary modernism. However, in the current era, it seems often that artists who display literary allusions risk being dismissed as pretentious or worse. Postmodernism has alerted us to the irony that undermines the earnestness of the modern era.

The painter Julian Schnabel has long aligned his work with literary figures, sometimes citing them within the painting as shards of texts or simply scrawling the names of well know literary figures across the canvas as a kind of signifier of allegiance to literary modernism. However, in the current era, it seems often that artists who display literary allusions risk being dismissed as pretentious or worse. Postmodernism has alerted us to the irony that undermines the earnestness of the modern era.

However, Baudelaire himself noted that by ‘modernity,’ he meant, “the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable…”

How can we argue against the poetics of such aspirations?

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department