Culture is a readymade, often treated as such by both artists and consumers of art. It is digital low-hanging fruit in a perpetual remix. In such remixes, we see the vestiges of history in a chaotic freefall. The history of art is bound up in history generally, and contemporary artists are participants in a similar remix and continual re-branding of art history itself.

Culture is a readymade, often treated as such by both artists and consumers of art. It is digital low-hanging fruit in a perpetual remix. In such remixes, we see the vestiges of history in a chaotic freefall. The history of art is bound up in history generally, and contemporary artists are participants in a similar remix and continual re-branding of art history itself.

The artist Kara Walker recently made a gesture toward the inherent power of monumentality and re-mixed the historically baroque Victoria Memorial outside London’s Buckingham Palace for her epicly-scaled Fons Americanus (2019) at the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London. The artist both reconsiders and critiques the very nature of public monuments as she simultaneously poses questions about the absence of bodies like her own in such monuments to (often European) history and ultimately to colonialism. The formal characteristics of historical monuments such as the Victoria Memorial, or others that pay homage to wars or military leaders, signal their endurance and privilege through materiality, scale, placement in public space, and other such contrivances.

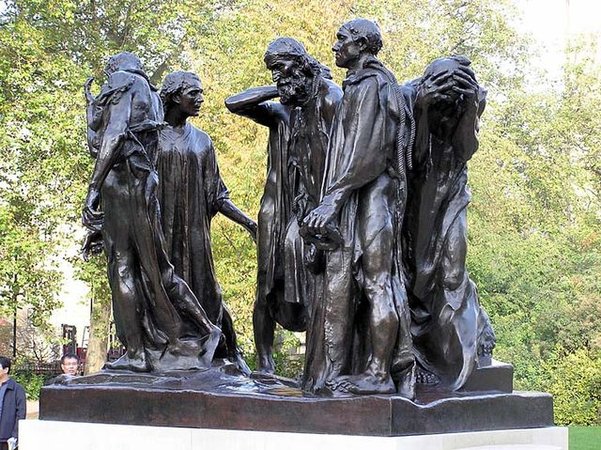

The artist Kara Walker recently made a gesture toward the inherent power of monumentality and re-mixed the historically baroque Victoria Memorial outside London’s Buckingham Palace for her epicly-scaled Fons Americanus (2019) at the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London. The artist both reconsiders and critiques the very nature of public monuments as she simultaneously poses questions about the absence of bodies like her own in such monuments to (often European) history and ultimately to colonialism. The formal characteristics of historical monuments such as the Victoria Memorial, or others that pay homage to wars or military leaders, signal their endurance and privilege through materiality, scale, placement in public space, and other such contrivances.  We see these formal conventions even in the posse of anti-heroes depicted in Rodin’s Burghers of Calais (1884), wrought as emaciated and beaten soldiers on their way to surrender, defeated yet noble in failure. Generally, such monuments stay put, embedded in their relationship to the state, a part of the narrative of the history of place. Under French law no more than twelve original casts of the works of Rodin may ever be made. While the 1895 cast of the group of six figures still stands in front of Parc Richelieu in Calais, France, the other casts are scattered quite literally around the world in places to which, in many cases, they have no logical connection.

We see these formal conventions even in the posse of anti-heroes depicted in Rodin’s Burghers of Calais (1884), wrought as emaciated and beaten soldiers on their way to surrender, defeated yet noble in failure. Generally, such monuments stay put, embedded in their relationship to the state, a part of the narrative of the history of place. Under French law no more than twelve original casts of the works of Rodin may ever be made. While the 1895 cast of the group of six figures still stands in front of Parc Richelieu in Calais, France, the other casts are scattered quite literally around the world in places to which, in many cases, they have no logical connection.

Walker’s work, like much contemporary art, pushes off from a place in which a desire for social justice is embedded within the work just as deeply as the choice of pigment, shape, or materiality. The imperative toward educating the viewer, making them a part of a new narrative, is often buttressed in exhibitions by accompanying wall texts, and, as the writer Michael Glover notes about Fons Americanus:

The text on the wall describes the work, in its all crazed, over-brimming totality, as something akin to a circus spectacle, at which we might stand, marvel, wonder, and point a finger. It is rooted in the past’s darkness, for sure, all our blameworthy acts of negligence, cruelty, and indifference, all our undeniable culpabilities.

Thus, we observe the work within the context of both the artist’s intentionality and the interlocutor’s placement of the work in a kind of art-historical mise-en-scène.

Following a recent lecture to my students about readymades, in the context of what I referred to as digressive modernism, one student shared a photo she had taken with her phone. The image of a battered bicycle missing wheels, bent and hanging off the rack by its lock, looked forlorn and tragic but quite familiar to anyone who lives around a college campus. However, this student presented the image to me as a found Dada piece, an absurd and startling object that reminded her of the disabled objects of Dada and Surrealist artists such as Man Ray or Marcel Duchamp. Her enthusiasm for this disfigured bicycle was about context and vision, new eyes brought to old situations, internally constructing narratives in which art can flourish, and where points of tangency present themselves as if out of the blue.

Perhaps postmodernism is still unable to make peace with the kind of earnestness we find in the work of artists such as Walker, Shimon Attie, Otobong Nkanga, and others. Earnestness, or further, naiveté, either willful or otherwise, suggests that one neglects pragmatism in favor of idealism. However, in the case of contemporary art, it may be a moral choice made in the hope that there is potential for change and evolution. For many contemporary artists, such emotions are held only slightly under the surface.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department