Art does not speak for itself. Actions don’t necessarily speak for themselves. Both require context and prior knowledge of the histories in which they are formed to fully resonate. Art that intends to implore a political consciousness has an especially elevated responsibility to tell more than show, though we know that gestures are not universal, nor is “art” immediately translatable across cultures and experience.

Art does not speak for itself. Actions don’t necessarily speak for themselves. Both require context and prior knowledge of the histories in which they are formed to fully resonate. Art that intends to implore a political consciousness has an especially elevated responsibility to tell more than show, though we know that gestures are not universal, nor is “art” immediately translatable across cultures and experience.

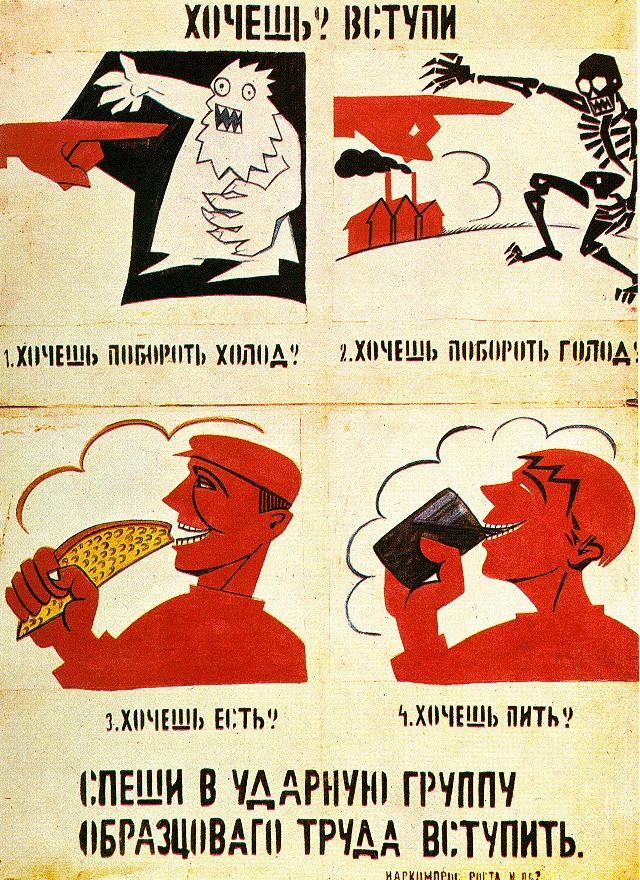

In the 1920’s, the term agitprop was used (largely by the Soviet Communist Party) to describe objects and images intended to control and promote any kind of ideological conditioning of the masses.  Largely optical, such highly designed and stylized broadsides, posters, and graphic imagery was intended to speak for itself and, further, for a particular political ideology. The juxtapositions of images were carefully constructed to imprint semiotically-specific takeaways, branding a particular political ideology through government-sanctioned works of art. Agitprop has come to refer to any cultural manifestation with an overtly political purpose and is used equally by all sides of contemporary political discourse. Ironically, or perhaps with no irony at all, the techniques of creating such immediately readable and politically loaded works of art have been appropriated by artists across all media and for a myriad of reasons.

Largely optical, such highly designed and stylized broadsides, posters, and graphic imagery was intended to speak for itself and, further, for a particular political ideology. The juxtapositions of images were carefully constructed to imprint semiotically-specific takeaways, branding a particular political ideology through government-sanctioned works of art. Agitprop has come to refer to any cultural manifestation with an overtly political purpose and is used equally by all sides of contemporary political discourse. Ironically, or perhaps with no irony at all, the techniques of creating such immediately readable and politically loaded works of art have been appropriated by artists across all media and for a myriad of reasons.

Political activism by artists is not a recent development; we learn about Picasso’s anti-war painting Guernica (1937) early on in a basic art history class.  However, Guernica was not immediately nor universally understood with the kind of nuance that has made it iconic. The gravitas of the painting comes from not only Picasso’s intentionality, but also from the public discourse surrounding the work by critics, viewers, historians, and others. The painted surface of Picasso’s anti-war gesture has simmered over time, and its meaning is largely a product of consensus.

However, Guernica was not immediately nor universally understood with the kind of nuance that has made it iconic. The gravitas of the painting comes from not only Picasso’s intentionality, but also from the public discourse surrounding the work by critics, viewers, historians, and others. The painted surface of Picasso’s anti-war gesture has simmered over time, and its meaning is largely a product of consensus.

As I think about the responsibility of art toward civic engagement and about the way in which artists perform a kind of global citizenship in the current era, I immediately think about the work of a number of artists who have appropriated the techniques of agitprop and of the often hyperbolic and politically charged forms of mass culture; of artists who have thoughtfully combined those techniques with postmodern uses of material and literary tropes of allusion, to create works that communicate in ways that are less cudgel than coaxing.

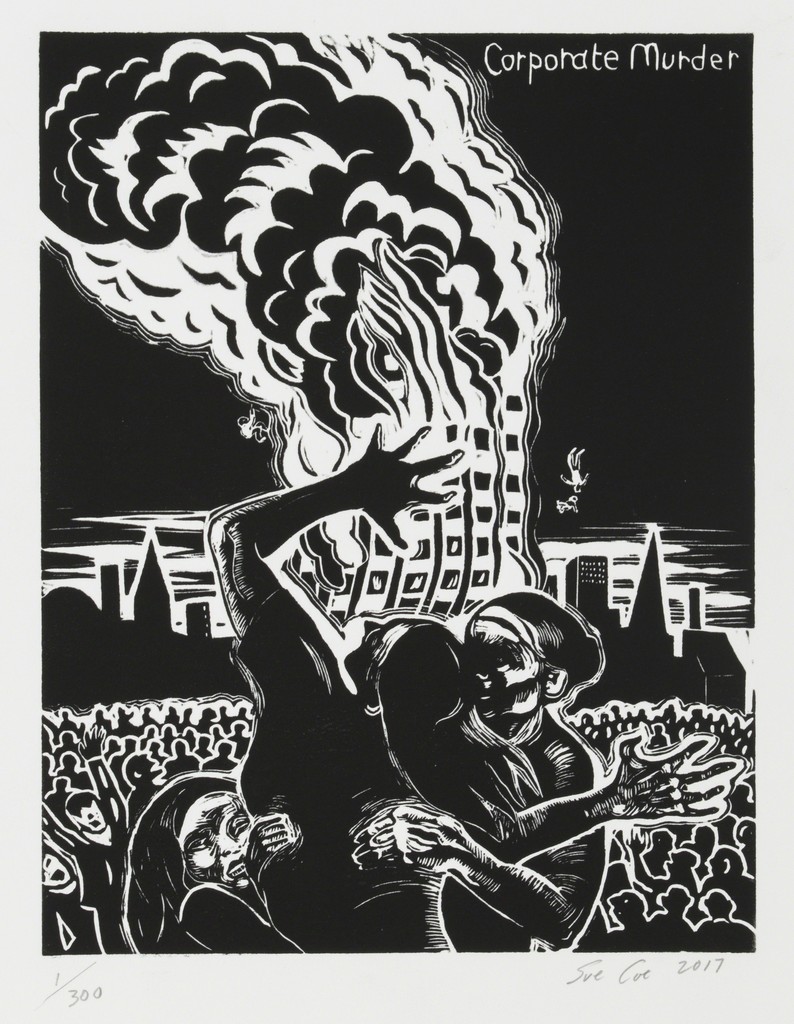

I think about Sue Coe, the UK-born artist, whose work has been described as graphic resistance, who deeply understands art’s “persuasive power,” and who has noted (as both an artist and a citizen, I would propose) that “neutrality is no longer a position we can afford.”

I think about Sue Coe, the UK-born artist, whose work has been described as graphic resistance, who deeply understands art’s “persuasive power,” and who has noted (as both an artist and a citizen, I would propose) that “neutrality is no longer a position we can afford.”

In the same context I think about the Chinese artist/activist Ai Weiwei, who has lived under government surveillance and periods of imprisonment for over a decade, who stated, “If anything, art is…about morals, about our belief in humanity. Without that, there simply is no art.”

In the same context I think about the Chinese artist/activist Ai Weiwei, who has lived under government surveillance and periods of imprisonment for over a decade, who stated, “If anything, art is…about morals, about our belief in humanity. Without that, there simply is no art.”

And I think about the Cuban-born artist Tania Bruguera, whose politically motivated interdisciplinary work across multiple media explores the relationship between art, activism, and social change, and addresses the social effects of political and economic power. Speaking about her work, Bruguera said, “I don’t want art that points to a thing. I want art that is the thing.” In 2010, Bruguera initiated Immigrant Movement International in Corona, Queens, New York, which functions as a community space that fuses art and education with a focus of empowering immigrants both at the personal level as well as politically; a space that embodies its beliefs and invites others to do the same.

And I think about the Cuban-born artist Tania Bruguera, whose politically motivated interdisciplinary work across multiple media explores the relationship between art, activism, and social change, and addresses the social effects of political and economic power. Speaking about her work, Bruguera said, “I don’t want art that points to a thing. I want art that is the thing.” In 2010, Bruguera initiated Immigrant Movement International in Corona, Queens, New York, which functions as a community space that fuses art and education with a focus of empowering immigrants both at the personal level as well as politically; a space that embodies its beliefs and invites others to do the same.

While Picasso’s Guernica might be the most well-known of the works mentioned here, the painting’s statement was fairly isolated in his overall practice. For the others here, Sue Coe, Ai Wei-Wei, and Tania Bruguera, activism and art are inseparable; they share a commitment beyond the production of the object or individual gesture that extends into the public sphere. Tania Bruguera describes herself as “an initiator” rather than an author. This distinction describes an ongoing process in which the creative act is a signifier and an extended relationship with the very people that she intends her art to affect.

Creating a public space for discourse through art is the privilege of a life lived where such rights exists. What we do in that space and with that privilege is the real work.

Douglas Rosenberg

Chair, UW-Madison Art Department